Hierarchical Structure of Peptides

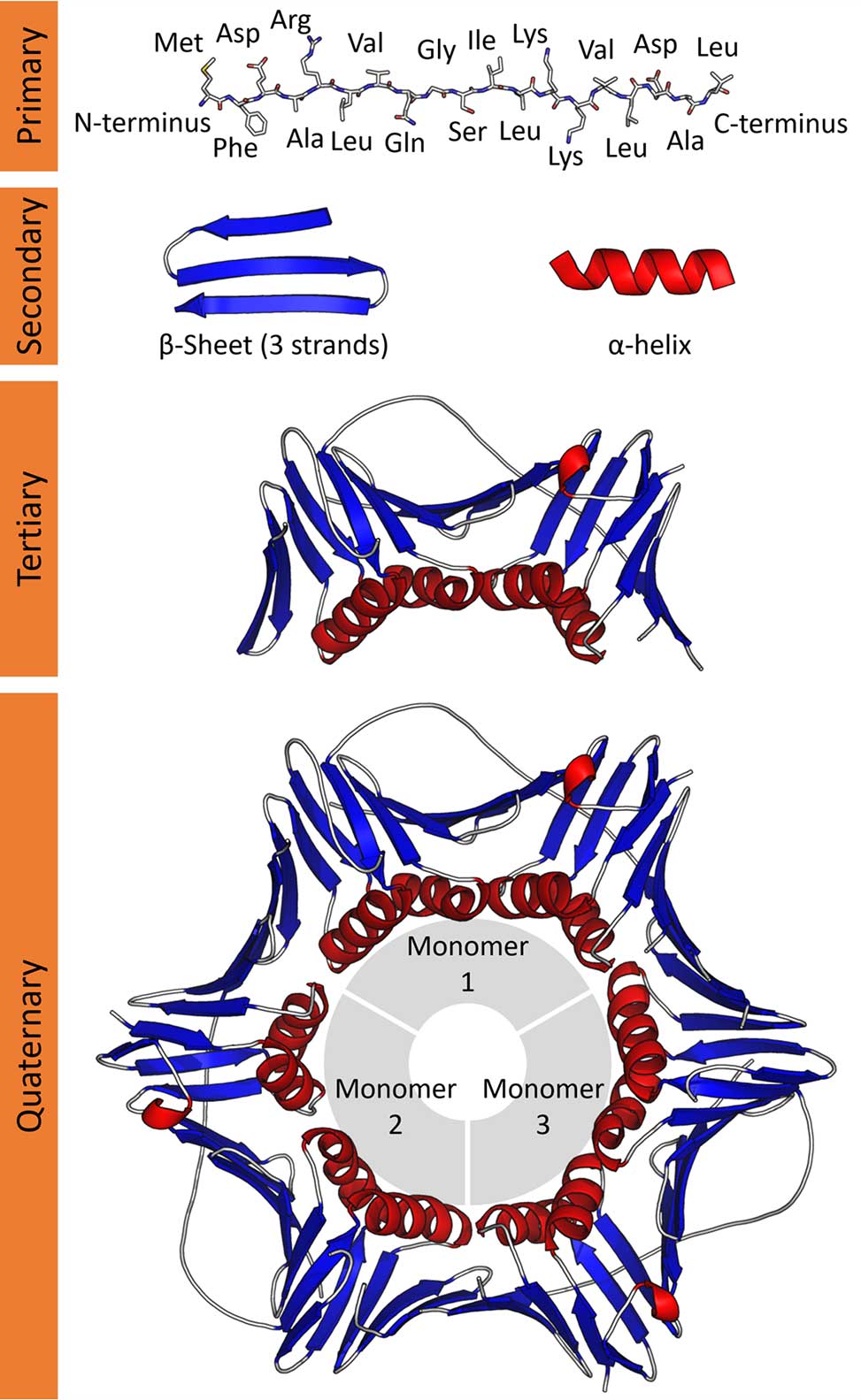

Peptides, like proteins, exhibit a hierarchical organization that influences their structure, function, and interactions within biological systems. This hierarchy begins with the primary structure, which refers to the linear sequence of amino acids in the peptide chain. As peptides fold and interact with their environment, they adopt more complex structures, including secondary and tertiary structures. The stability and function of peptides depend heavily on these structural levels, as they determine the peptide’s conformation, reactivity, and potential biological activity.

Primary Structure

The primary structure of a peptide refers to the linear sequence of amino acids connected by peptide bonds. This sequence is unique to each peptide and is determined by the genetic code during protein translation. The amino acid sequence dictates how the peptide will fold and interact with other molecules, as the chemical properties of the side chains (R-groups) of each amino acid influence the peptide’s overall behavior.

In synthetic peptide chemistry, the primary structure is carefully designed and assembled during processes such as Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis, SPPS. 1 Each amino acid is added sequentially, and protecting groups, like Fmoc, fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl, are used to ensure that the desired sequence is achieved without unwanted side reactions. The primary structure is fundamental because any change in the amino acid sequence, even a single substitution, can alter the peptide’s stability or biological function. For example, the substitution of valine for glutamic acid in hemoglobin gives rise to sickle cell disease, illustrating how changes at the primary structure level can lead to profound physiological effects.

Secondary Structure

The secondary structure refers to the local folding patterns of the peptide chain, primarily stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the backbone atoms. Two of the most common secondary structure motifs are the alpha-helix and beta-sheet. These structures are critical for the formation of more complex protein conformations and are often found in the functional domains of proteins and peptides. 2

The alpha-helix is a right-handed coil in which every backbone carbonyl oxygen forms a hydrogen bond with the amide hydrogen of the amino acid four residues earlier. This structure is compact and provides stability due to the repetitive hydrogen bonding pattern. 3 Alpha-helices are commonly found in transmembrane domains of proteins and in peptides that interact with DNA or other biomolecules. Conversely, beta-sheets consist of extended peptide chains arranged side by side, connected by hydrogen bonds between backbone atoms in neighboring chains. These sheets can be either parallel or antiparallel, depending on the direction of the peptide chains. Beta-sheets are often found in structural proteins, such as silk fibroin, and play important roles in forming the rigid, fibrous components of tissues.

Studies on peptide folding and stability often rely on techniques like circular dichroism, CD, spectroscopy, which can measure the degree of alpha-helical or beta-sheet content in a peptide. Understanding how peptides adopt these secondary structures is essential for the design of synthetic peptides, particularly those intended for use in drug delivery or material science, where stability and structure are key to function.

Tertiary Structure

The tertiary structure represents the overall three-dimensional conformation of a peptide, resulting from interactions between side chains, R-groups, that are distant from each other in the primary sequence. These interactions include hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, and disulfide bonds between cysteine residues. The tertiary structure is essential for the biological activity of many peptides, as it determines how the peptide interacts with other molecules, including receptors, enzymes, and other peptides or proteins.

Peptides are typically more flexible than larger proteins, and their tertiary structure is often less rigid. However, some peptides can adopt stable conformations due to the formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic core packing, or covalent linkages like disulfide bridges. For instance, insulin’s biological activity depends on the proper formation of disulfide bridges between its chains, which stabilize its structure and allow it to function effectively in regulating blood glucose levels. The role of disulfide bonds in stabilizing peptide structures is widely studied, especially in the context of therapeutic peptides, where stability in the bloodstream is a key concern.

Quaternary Structure in Peptides

Although quaternary structure is more commonly associated with larger proteins, some peptides can also form multimeric complexes, exhibiting quaternary structures. Quaternary structure refers to the assembly of multiple peptide or protein subunits into a larger, functional complex. These subunits are held together by non-covalent interactions, including hydrophobic interactions, ionic bonds, and sometimes disulfide bridges. An example of a peptide with quaternary structure is insulin, which forms a hexameric structure in the presence of zinc ions for storage in the pancreas. Upon secretion, it dissociates into its active monomeric form to regulate blood sugar levels.

Other examples of quaternary structures in peptide systems include fibrils formed by amyloid-beta peptides in Alzheimer’s disease. These fibrils are composed of stacked beta-sheets that self-assemble into fibrous aggregates, demonstrating the pathological role that quaternary structures can play in neurodegenerative diseases. Understanding the factors that influence peptide aggregation and multimeric assembly is critical for the development of peptide-based materials and the design of therapeutic agents targeting amyloid-related conditions.

Conclusion

The hierarchical structure of peptides, from the primary sequence to the tertiary and quaternary levels, is fundamental to understanding their function, stability, and interactions. Each level of structure contributes to the overall behavior of the peptide in biological and synthetic contexts. Advances in peptide synthesis, particularly through methods like Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis, SPPS, and Liquid-Phase Peptide Synthesis, LPPS, have enabled researchers to control these structural elements with precision, paving the way for new therapeutic applications and biomaterial innovations.

Citations, Credits, & Links

1. Merrifield, Robert B. “Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis. I. The Synthesis of a Tetrapeptide.” Journal of the American Chemical Society, vol. 85, no. 14, 1963, pp. 2149-2154. doi:10.1021/ja00897a025.

2. Branden, Carl, and John Tooze. Introduction to Protein Structure. Garland Science, 1999.

3. Pauling, Linus, et al. “The Structure of Proteins: Two Hydrogen-Bonded Helical Configurations of the Polypeptide Chain.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 37, no. 4, 1951, pp. 205-211.

4. Image credit: Thomas Shafee – Own work, CC BY 4.0,