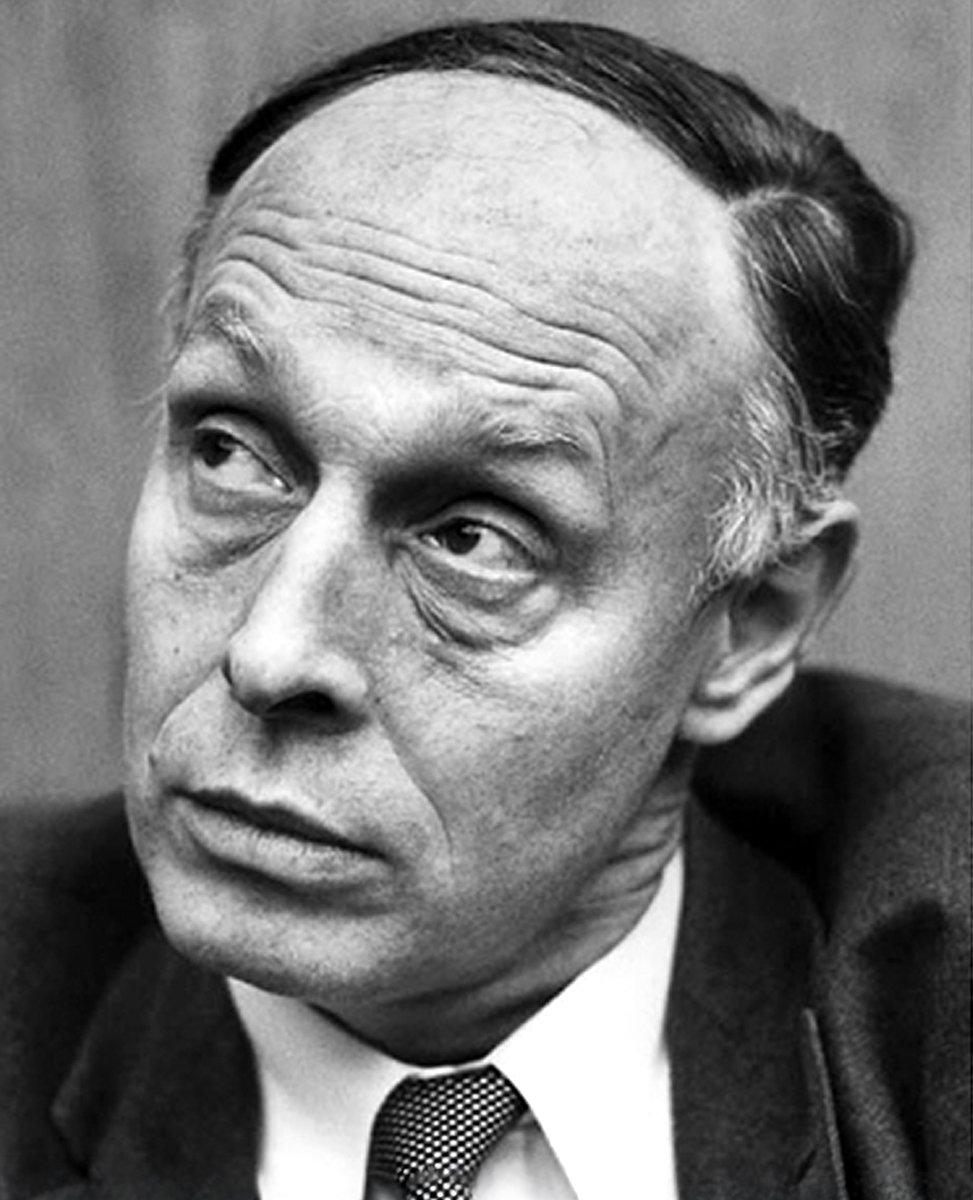

Klaus Hofmann

Klaus Hofmann was a peptide chemist whose synthesis of biologically active ACTH fragments established fundamental principles of hormone structure-function relationships and receptor binding. His five decades of research at the University of Pittsburgh transformed understanding of how peptide hormones interact with their targets, demonstrating that dramatic modifications to peptide structure could be made without substantially altering biological potency.

Born February 21, 1911, in Germany, Hofmann lost his father while still an infant. His mother returned with her one-year-old son to her family home in Switzerland, where he would grow up determined to pursue science despite the family's business orientation. He studied steroid chemistry at the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich under Leopold Ružička, developing a friendship with fellow faculty member Tadeus Reichstein from whom he learned rigorous laboratory technique. Both Ružička and Reichstein would later receive Nobel Prizes. As a doctoral student, Hofmann synthesized a dehydroandrosterone derivative that represented a prototype for the birth control pill, though the biological basis for reproduction was not yet understood.

Image by Dr. Frances Finn Reichl - This is a photo that I received from the widow of Klaus H Hofman, Dr. Frances Finn, given to me for the express purpose of uploading onto Dr. Hofmann's Wikipedia page which we jointly wrote most of. An email confirming this will be forthcoming. IT HAS NEVER BEEN PUBLISHED ANYWHERE BEFORE., CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

For postdoctoral experience, Hofmann traveled to the United States to work with Max Bergmann at the Rockefeller Institute. There he synthesized lysine analogs and proved that trypsin cleaves peptide bonds specifically at lysine residues, an attribute that made trypsin the enzyme of first choice in protein sequence determination. He then moved across the street to Vincent du Vigneaud's laboratory, where he applied chromatographic techniques learned in Zurich to isolate and crystallize biotin. This work initiated a career-long interest in sulfur-containing biologically active structures.

What was meant to be a brief American stay became permanent when World War II erupted. Switzerland, surrounded by hostile forces, advised Hofmann, an officer in the Swiss militia, not to return for the duration. He spent the war years as a guest researcher at Ciba Pharmaceutical Company in New Jersey, then joined the University of Pittsburgh in 1944 as the institution was building its research reputation. Within eight years, the dean invited him to become chairman of the new Biochemistry Department in the School of Medicine.

At Pittsburgh, Hofmann fell in love, in his own words, with a molecule known to stimulate the adrenal cortex to produce the steroids that had fascinated him in Reichstein's laboratory. That molecule was ACTH, and the relationship proved lifelong. With the 39-amino-acid sequence of ACTH newly determined and evidence suggesting that only the first 24 residues were needed for full activity, Hofmann's group developed methods for incorporating arginine into peptides. Their efforts led first to the synthesis of α-MSH, corresponding to the first 13 amino acids of ACTH, and then in 1960-1961 to a tricosapeptide comprising the first 23 amino acids that possessed essentially full biological activity. The New York Times reported the achievement under the headline "Scientists Make ACTH Substitute," calling Hofmann an "expert on synthesis of body compounds."

Hofmann recognized that structure-function studies with ACTH were complicated by the necessity of assessing activity in whole animals. When Fred Richards discovered in 1959 that the enzyme subtilisin could cleave ribonuclease A into two inactive fragments, S-peptide and S-protein, that regained full activity when mixed together, Hofmann saw a model system for studying peptide-receptor interactions. His systematic evaluation of how each amino acid in S-peptide contributed to binding with S-protein yielded insights that correlated remarkably with ACTH analog behavior: only a portion of the chain was essential for activity, certain residues could be substituted without effect, and specific modifications could create antagonists rather than agonists.

In 1964, Hofmann resigned as department chairman to direct his own research institute at Pittsburgh, the Protein Research Laboratory, where he pursued increasingly sophisticated studies. His group isolated plasma membranes from beef adrenals and demonstrated that substituting phenylalanine for tryptophan at position 9 produced a peptide that bound the ACTH receptor without activating it, creating a true ACTH antagonist. This work on how peptides bind to proteins he considered his greatest achievement.

Hofmann's career came full circle when he combined his early biotin expertise with peptide chemistry. After a sabbatical in Helmut Zahn's laboratory in Aachen learning insulin modification techniques, he attached biotin to insulin's lysine residues, creating derivatives that would bind avidin-Sepharose columns. Using this approach, his group successfully isolated a fully active insulin receptor in 1984. His final work attempted the same strategy for the ACTH receptor, but declining health intervened.

Hofmann received the American Peptide Society's Alan E. Pierce Award in 1981. His many honors included the Borden Medal and Chancellor's Medal from the University of Pittsburgh (both 1963), election to the National Academy of Sciences (1963), the Alexander von Humboldt Senior Scientist Award (1976), and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences Fellowship (1983). A demanding but caring teacher, he reinvented his biochemistry course for first-year medical students each time he taught it. He advised colleagues: "You're wrong to go after prizes; the only real way to do science is for the fun of it."

Klaus Hofmann died on December 25, 1995, in Pittsburgh at age 84.